Heroes of Irish Science - Jocelyn Bell-Burnell

The Irish Times today began a new series of articles on the Heroes of Irish Science. The first looks at the life and works of the Irish astronomer Jocelyn Bell-Burnell, who discovered pulsar stars, and is written by Ronan McGreevy.

THE

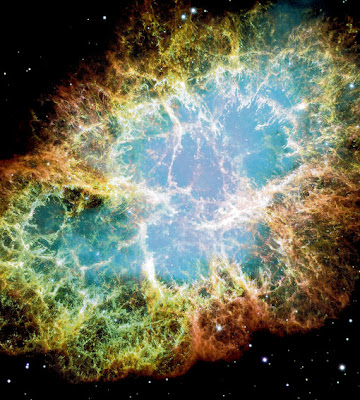

ASTRONOMER Jocelyn Bell-Burnell is one of Ireland’s most accomplished

scientists. While still a research student she discovered pulsars and

went on to become a distinguished scientist who made important

astronomical discoveries.

She is a true hero of Irish science for her many accomplishments and

for her ongoing contribution to a better public understanding of

science. Her discovery of pulsars is one of the famous stories in

science and it is also one of the most infamous.

In 1967 Jocelyn

Bell was a 24-year-old PhD student from Belfast, reading radio astronomy

at Cambridge University and examining newly-discovered quasars

(quasi-stellar radio sources), incredibly bright and incredibly compact

structures of light and energy at the centre of galaxies. She spent

months reviewing print-outs from a radio telescope when she noticed

small rhythmic blips on the paper one night in July.

The blips

turned out to be signals from a radio source which had never been

conceived before, let alone discovered. At first it was called – half in

jest, half with a nod to the remote possibility that they might be

signals from intelligent alien life forms – Little Green Man 1 (LGM-1).

The signals turned out to be pulsars (pulsating radio stars). The announcement was made to an astonished scientific world in

Nature magazine in 1968. Six years later Prof Bell-Burnell (she

married fellow scientist Martin Burnell in 1968), was denied a Nobel

Prize for the discovery. Instead, her supervisor, Prof Antony Hewish,

became the first astronomer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in physics,

which he shared with Martin Ryle, the then Astronomer Royal and pioneer

of radio telescope technology.

It remains a

cause célèbre of modern science. Here was a young scientist and

a woman in a male-dominated profession, denied the ultimate prize in

science. Though many took up the cudgels on her behalf, Bell-Burnell has

always been admirably philosophical about it. Research students do not

usually win Nobel Prizes, however noteworthy their discoveries.

Hewish

himself described it as crediting the discovery of the New World to the

look-out who first spotted land on Christopher Columbus’s expedition,

though Bell-Burnell had a part in designing the experiment.

The

decision was not fair, she says, but a lot of things in life are not

fair and besides, she has had a successful career, Nobel Prize or

No-Bell Prize, as it was deemed at the time. “It is an awful waste of

time and energy to be grieving over something that you can’t do anything

about,” she says.

Bell-Burnell had already moved several times

after leaving Cambridge by the time the Nobel Prize was awarded in 1974.

After a spell at the University of Southampton, she joined the Mullard

Space Science Laboratory at University College London working on the

Ariel 5 satellite which was launched in 1974 to study X-ray astronomy. “I was very, very lucky. It (

Ariel 5 ) was hugely successful. I found myself wishing

somebody would invent a Lord’s Day observant satellite so we could get a

day off. It was phenomenally exciting.”

There have been many

compensations, not least a slew of honours, most notably when she was

made a Dame in 2008 for her work in science.

It was followed by

her becoming the first female president of the Institute of Physics,

which operates in the UK and Ireland. She has been a recipient of the

Oppenheimer Prize and the Michelson Medal and holds several honorary

doctorates.

She is also known for her championing of women in

science and for her Quaker faith, which remains unmoved by the appliance

of science. She has always been an advocate for the idea that science

and faith can, as she put it, sit “lightly with each other” and it is

part of the Quaker faith to believe that you can get closer to God by

observing his creation.

She is critical of the well-known atheistic scientist Richard Dawkins saying he has a “fundamentalist view” of the subject.

“He

believes science can prove anything. If it is not amenable to

scientific proof, it doesn’t exist. If you care for a young child, for

instance, is that science?”

Before Christmas she gave a lecture in

Trinity College Dublin about the former planet Pluto. By her admission

she was no expert on the subject of this cold and remote world when she

was asked to chair a meeting of the International Astronomical Union in

2006 at which Pluto was downgraded to a minor planet.

Several

hundred people turned up to hear her recount the often farcical

circumstances in which delegates made the decision on the last day of

the conference when many of the planetary scientists had gone home.

However, with the benefit of hindsight, she still believes it was the

right decision taken for the wrong reasons.

As perhaps the most

famous living Irish astronomer, Bell-Burnell has been invited to chair

several events at the Euroscience Open Forum 2012 meeting taking place

next July in Dublin. She will host discussions on exoplanets and black

holes, a subject very close to that of pulsars. She will also give a

keynote address on a topic yet to be decided.

Read the original article here (which includes a bried introduction to pulsars).