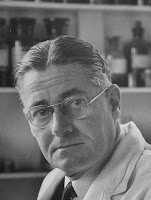

Howard Florey - Penicillin Pioneer

Howard Walter Florey was born on the 24th September 1898 in Adelaide. Through his work on penicillin he was to become indirectly responsible for the saving of millions of lives across the world, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine in 1945. So how is it then that, outside his native Australia, Florey’s name is so little known – whilst that of Sir Alexander Fleming is immediately associated with the ‘discovery’ of penicillin?

In 1938 Florey started working with the biochemist Ernst Chain in Oxford University, looking at naturally occurring substances which were capable of killing bacteria. They started off investigating the properties of lysozyme, a substance found in human tears and saliva, but then moved on to investigate antibacterial substances made by micro-organisms. During this research Chain came across an article written by Alexander Fleming ten years earlier in which he noted that in one of his Petrie dishes bacterial colonies did not grow in the vicinity of a particular mould (fungus) called Penicillium notatum. Fleming surmised that the mould must produce an antibiotic substance – which he tentatively named ‘penicillin’, although he was not able to isolate any for direct use as a medicine.

Although highly regarded for his intellect, Florey was viewed as something of a ‘colonial outsider’ in Oxford and, in a move that was ahead of its time, he set up a team of scientists to work on how to isolate, purify and clinically administer penicillin. On Saturday 25th May 1940 Florey’s team injected 8 mice with lethal doses of streptococci bacteria – 4 mice were subsequently treated with penicillin and 4 were left untreated as ‘controls’. By Sunday the 4 treated mice had recovered, and the 4 others were dead. Publication of these results spurred the British government, now embroiled in the Second World War, to take an interest in Florey’s work.

In 1941 the new drug was tested on Albert Alexander, a policeman who’s face had become infected following a scratch from a rose thorn. He was near death, and had already had one eye removed and the other lanced due to a build up of septic pus. After just one day of treatment he began to recover, but the supplies of penicillin soon began to run out despite desperate attempts to recycle it from the patient’s urine. Sadly Alexander had a relapse and died, and this led the team to concentrate future trials on children who, being smaller, would require less of the drug. By 1943 Florey was able to try penicillin on wounded soldiers in N. Africa – with seemingly miraculous results.

Today there are over 60 different types of antibiotic in common use, but new types are continually needed due to bacteria mutating to become antibiotic resistant – examples being the various hospital ‘superbugs’ such as MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus).

Comments